DIAMOND

ALKALI/SHAMROCK

PAINESVILLE

WORKS

The Diamond's Painesville Works and

the Fairport, Painesville & Eastern were closely connected to each other throughout

their histories: both the plant and the railroad were constructed and began

operations at the same time; in the decades following their creation, as the

Works grew, so did the FP&E; and unfortunately, when the Works closed the

FP&E was not far behind it in fading into history. With the plant being so closely tied to the

railroad—not to mention being the railroad's largest customer by far for

64 years of its 72-year operating existence—I believe it is a necessity to

discuss in some detail the Diamond's Painesville Works as part of any

discussion about the FP&E.

Below

is some information I've gathered about the Diamond, and I've organized into

three sections: a historical background of the Diamond Alkali/Shamrock

Corporation in general, a description of some of the manufacturing processes at

the Works circa 1956, and a chronology of the different portions of the Works.

Historical Background

I have found two very good general histories of

the Diamond Alkali/Shamrock Corporation; both are entries from editions of the International

Directory of Company Histories, and both can be read on the internet. From the International Directory of

Company Histories: Volume 7 there is an entry for Maxus Energy Corporation

which, as the successor to the Diamond Shamrock's oil production and

exploration divisions, includes a good amount of historical background

information on the Diamond (click here

to read the entry). From the International

Directory of Company Histories: Volume 31 there is an entry for Ultramar

Diamond Shamrock Corporation which, as the successor to the Diamond Shamrock's

oil refining and marketing divisions, includes an even larger amount of

historical background information on the Diamond (click here

to read the entry). Though the

information in these articles covers the same territory, they are not

identical, so it is very worthwhile to read both of them.

For those who prefer

something shorter I wrote the following brief version of the Diamond's history

based on the two articles linked above plus excerpts from the books Glass: Shattering Notions, Strategies for

Declining Businesses, Encyclopedia of Chemical Processing and Design:

Volume 51, and Applied Industrial Economics.

Diamond Alkali was founded in 1910 by three

glass-making companies (Macbeth-Evans Glass Co. of Pittsburgh, C.L. Flaccus

Glass Co. of Pittsburgh, and Hazel-Atlas Glass Co. of Wheeling, WV) with the

purpose of manufacturing soda ash—a major raw material in glass

production. The new firm was

incorporated on March 21, 1910 in West Virginia, with the company's

headquarters established in Pittsburgh.

With a capitalization of $1.2 million, a soda ash plant was built in

Painesville Township, Ohio. The plant began operation in 1912; however, it

wasn't until the demand for glass dramatically increased with the start of

World War I that the company's business boomed.

After the war the company expanded into other

product areas: production of bicarbonate of soda began in 1918; in 1924-25 the

plant was expanded to produce calcium carbonates, cement, and coke; and in 1929

production of chlorine was begun.

To ensure the company would not stagnate a

research program was begun in 1936, and in 1942 Diamond Alkali established a

research laboratory. One result of the

company's 1936 research program was the production of magnesium oxide. When magnesium became an important ingredient

in incendiary bombs during World War II, the Diamond was recruited by the U.S.

government to build and operate a magnesium plant for the Defense Department.

In the decade after World War II the company

continued to expand its product range in Painesville, but also expanded

geographically through acquisitions and new plants—including a second

chlorine/caustic soda plant in Houston (Deer Park). Though some of the acquisitions and new plants

increased the production capability of chemicals the Diamond already made, some

of the newly acquired companies and new facilities had the effect of

diversifying the company's products to include such things as agricultural

chemicals and plastics.

Reflecting the importance of its operations in

Painesville, in 1948 the corporate headquarters was moved from Pittsburgh to

Cleveland. The company continued its

emphasis on research by opening the Diamond Technical Center in Fairport Harbor

in 1951, and by opening the Diamond Research Center in Concord Township in

1961.

In the 1960s Diamond Alkali's expansion

continued with acquisitions of numerous chemical and plastics companies. During this decade the company also created a

specialty chemicals division, expanded production of industrial chemicals and

plastics at its existing plants, and built new chlorine/caustic soda and PVC

plants in Delaware.

Recognizing the current trend in petrochemical

combines—and not wanting to be acquired by a large oil company—Diamond Alkali

made a pre-emptive move by approaching Texas-based Shamrock Oil & Gas with

a merger plan in the mid-1960s; in 1967 the two companies merged to form

Diamond Shamrock Corporation.

In the 1970s Diamond Shamrock continued to

grow—especially in the areas of specialty chemicals, petroleum, and

plastics. Though the company was

becoming more focused on these other areas, industrial chemicals were still

important, and in 1974 construction began on a new chlorine/caustic soda plant

at Houston (Battleground). But despite

the company's continued growth, the original core product of the company, soda

ash, the primary product of the Painesville Works, was in decline.

Though soda ash can be made synthetically from

limestone and salt—as was done at the Painesville Works—it also occurs

naturally. Mining natural soda ash is

mechanically easier than producing synthetic natural soda, uses less energy,

and causes less pollution. However, since

most of the natural soda ash deposits in the U.S. were out west, while most of

the soda ash customers were located east of the Mississippi (along with the

synthetic soda ash producers), the cost of transporting natural soda ash across

the country made it more economical for customers to buy soda ash from

synthetic producers. This economic

equation changed significantly in the early 1970s: in part because of higher

costs from increasingly stringent pollution control standards, but mostly

because of skyrocketing energy costs—and since energy was 50% of the cost of

producing synthetic soda ash, when energy costs soared, synthetic producers

could no longer compete with natural producers.

The result was that between 1972 and 1975 four of the eight major

synthetic soda ash plants in the country had already closed down.

In 1976 Diamond Shamrock added its soda ash

plant to that group when it announced in June that it was closing the entire

Painesville Works at the end of the year.

Though the facility made other chemicals, there were several factors

that added up to closing the entire Works:

a) the soda ash

produced at the plant was not all shipped to customers: 25% was used internally

at the Works to manufacture many other chemicals, which meant that closing down

the soda ash unit consequently ended the operations of other units

b) the same factors

that adversely affected the manufacture of soda ash—the high costs of both

energy and environmental controls—also adversely affected the Works overall

c) the Works was an old

facility (presumably in comparison to the company's other, newer industrial

chemical plants such as Battleground in Houston)

The closing of the

Painesville Works was indicative of the new direction Diamond Shamrock was

heading, for in 1979 the company announced its intention to become an energy

company rather than a chemical company.

In a move that demonstrated this new purpose, Diamond Shamrock's

headquarters was moved from Cleveland to Dallas later that year. Over the next several years the company

divested itself of non-energy divisions while continuing to acquire coal and

petroleum companies. The ultimate

divestiture occurred in 1986 when the company sold its all of its remaining

chemical business units to Occidental Petroleum. The following year the energy production and

exploration divisions of the company were split off to form Maxus Energy, and

Diamond Shamrock became strictly a petroleum refining and marketing company.

Over the next decade

Diamond Shamrock continued to grow and have success in petroleum refining and

retail petroleum sales. In 1996, the

company merged with Ultramar to become Ultramar Diamond Shamrock (UDS); however,

after this merger the company suffered one financial setback after another due

to the oil price crash of the late 1990s.

In 2001, UDS was bought out by Valero Energy, and the Diamond Shamrock

name disappeared into the history books.

The Diamond Story

A few years ago I was fortunate to

win an auction on eBay for a booklet about the Diamond's Painesville Works

called The Diamond Story at Painesville.

There is no author (though there is an introduction by M.O. Kirp, Works

Manager), and there is no date in it.

However, from reading through it and comparing certain facts with the

general histories referenced above, I have figured out that it is from

1956. When I showed this booklet to my

mother (her father—my grandfather, Bruce Merrill—worked as a millwright at the

Diamond from 1938 to 1975), she said that this was probably the booklet that

was used when the Diamond did a large-scale public open house when she was a

young girl.

The

booklet is full of information about the Works overall as well as the specific

manufacturing processes of different units in the Works—much of which I am

sharing here in transcription form (unfortunately, because of webspace

limitations, I cannot display scans of the entire booklet).

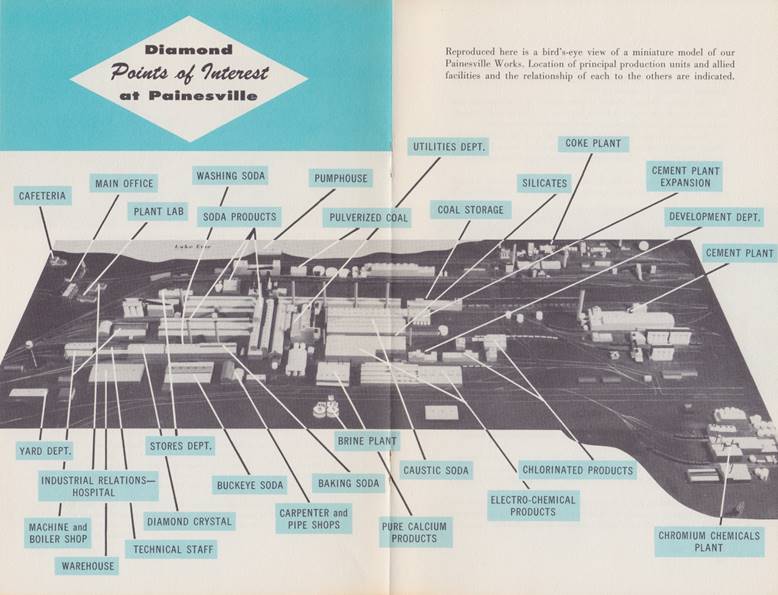

Before reading through

the transcribed information, let me draw your attention to the picture below:

this is a picture of a model of the Works that takes up the 'center spread' of

the booklet. This picture will be handy

to refer back to when reading through all the information I will be sharing on

this webpage from this point forward.

The only major facility that the picture does not show is the Diamond

Magnesium Plant, which was located further east on Fairport-Nursery Road (the

road depicted on the bottom/southern edge of the plant). By the way, this model still exists and is

being kept at the Fairport Harbor Marine Museum & Lighthouse.

Click on the image to view

a larger version.

Why Painesville Was Selected as Plant Site

Diamond's

first plant was built in 1912 at Painesville, on the southern shore of Lake

Erie, about 30 miles east of Cleveland.

Of the many sites studied for the new venture, this area was finally

selected in the belief the combination of its natural resources and man-made

advantages provided an ideal location with respect to supplying soda ash to the

glass industry, whose plants were then concentrated in western Pennsylvania,

southeastern Ohio and northern West Virginia.

The

area's attributes included among others:

1. A virtually

inexhaustible supply of salt—a strata about 500 feet thick and between 2,000

and 2,500 feet below the surface;

2. Availability of water

from Lake Erie, in unlimited quantity, for both product-processing and

equipment-cooling purposes, and

3.

Dependable,

economical transportation, via water and rail routes, for both delivery of

limestone from Michigan and coal from southern Ohio and West Virginia to the

plant, and shipment of finished products to consuming markets.

Here

in Painesville, then, four workhorses of modern applied industrial chemistry's

workaday world—salt, limestone, coal, and water—could be effectively harnessed

and products derived from them economically assembled.

Indeed,

this location proved to be a fortunate selection. Developments of the past quarter-century have

confirmed the wisdom of our founders' choice in many ways. Most important, aside from affording easy

access to these essential materials for alkali production, Painesville has

enabled Diamond to distribute, economically from one location, to the tri-state

area of Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia; to the chemical orbit in the New

York-New Jersey-Philadelphia-Baltimore section, and to chemical plants in the

Midwest, particularly such centers as St. Louis, Cincinnati and Chicago.

Production

of soda ash started early in 1912, and customer demand proved so strong that

within three years capacity was increased to 800 tons daily. A portion of the new capacity, however, was

installed for caustic soda manufacture, launched in 1915. During World War I, in response to Government

request, Diamond doubled its caustic soda production early in 1918. The Company also embarked upon the

manufacture of bicarbonate of soda the same year.

Integration Proved Prime Consideration in

Early Days

Because

Diamond's founders were enamoured of the chemical industry's growth

possibilities, their long-term aim was to build an integrated operation not

only for producing the so-called "basic alkalies"—soda ash, caustic

soda and bicarbonate of soda—but also for utilizing a portion of them for

further processing and "upgrading" into other versatile chemicals.

This

expanding perimeter of new products thus called for new facilities and new

ideas; both followed at a steady pace during the next quarter-century, with

diversification and expansion sparked principally by more efficient and broader

usage of raw materials.

So,

in 1924, coke ovens were installed and an accompanying by-product plant built

to recover ammonia, gas and tar distillates.

Gas is used for fuel, ammonia and coke are required for soda ash. Benzene, toluene and related hydrocarbons are

derived from the tar distillates. This

installation enabled Diamond (1) to overcome a then-constantly-recurring

shortage of coke (used in soda ash production) and (2) further broaden its

product picture by the addition of premium-grade coke for foundries.

In

1925, facilities were established for producing precipitated, free-flowing

calcium carbonate of exceptionally high purity, a co-product of caustic soda by

the old lime-soda process. In 1937,

these facilities were further expanded.

Waste

limestone screenings not adaptable for soda ash manufacture led in 1925 to the

construction of a Portland cement plant.

Today, it is the leading factor in Northern Ohio's cement industry.

In

1926, an operation for packaging sal soda, lye and baking soda for household

use was organized.

Two

important developments brought this initial integration era in Diamond's

history to a close: manufacture of chlorine and production of bichromate of

soda. Because of Diamond's own salt beds

and power-generating facilities at Painesville, chlorine production was a natural

corollary development. Accordingly, and

electrolytic plant was put "on stream" in 1929. Its capacity has since undergone a number of

sizable expansions.

Soda

ash is an essential raw material for sodium bichromate; hence, it was equally

logical in this instance for Diamond to become interested in producing this

chemical. Production was consequently

started in 1931.

Other

significant growth moves followed in the ensuing years prior to World War

II. They included the manufacture of

carbon tetrachloride (a chlorine-derived solvent), and the development of

specialized alkaline detergents for use in the dairy and bottling industries as

well as in laundries.

Two-Fold War Production Job Accomplished

As

you might expect, Diamond contributed in diverse ways to the nation's military

production program during the war period.

At Painesville, this effort involved the manufacture of magnesium metal

for aircraft production, and the development and manufacture of "Chlorowax,"

a chlorinated paraffin.

Early

in 1941, when national defense quickly became "the order of the day"

along the industrial front, the Government requested Diamond to make metallic

magnesium. Because this operation

entails electrolytic decomposition of magnesium chloride, Diamond found it

necessary to develop a method for producing this material.

Diamond

engineers accomplished this objective through adapting certain portions of the

basic alkali process and applying these adaptations to the treatment of

dolomitic limestone. As Diamond was

getting ready to take over this production assignment, the Defense Plant

Corporation constructed a plant adjacent to our Painesville Works. Completed and put into operation in

September, 1942, this defense production facility soon exceeded its rated

capacity.

Operated

by Diamond through the Diamond Magnesium Company, an affiliate organized

specifically to carry out this mission, this plant remained in operation until

late 1945, long after other wartime magnesium production facilities had closed

down. (It received the Army-Navy

"E" Award for "excellence in war production.") When the Korean crisis came in 1951, the

Diamond Magnesium Plant was reactivated at Government request, and remained in

operation until mid-1953, when it again was "mothballed"; it is now maintained

as a stand-by facility for future defense needs.

Chlorowax,

a synthetic resin made from paraffin wax and chlorine, is an original Diamond

research development. Almost immediately

after its introduction, the material became widely used in the manufacture of

fire-retardant paints for application aboard Navy vessels, in the production of

tracer bullets, and in formulating flame-resistant compounds for impregnating

military textiles, such as camouflage nets, tents, fabrics, etc.

What We Make at Painesville …

Soda Ash

Production of soda

ash comprises a major operation of the Painesville Plant. To make this versatile basic chemical,

limestone from Michigan and coke from our own Coke Plant are mixed in proper

proportions and charged into large kilns to produce carbon dioxide gas and

lime. Salt is recovered as a solution

from a nearby deposit some 2,000 feet below ground level.

This solution, or

brine, is purified, saturated with ammonia gas, then carbonated in towers with

the gas recovered from the lime kilns. A

slurry leaving the bottom of the carbonating towers contains ammonium chloride

in solution and sodium bicarbonate as a solid.

The solid crude "bicarb" is then separated from the ammonium

chloride solution on rotary vacuum filters.

The ammonium

chloride solution is pumped to distillation columns, or lime stills, where the

lime, as a calcium hydroxide slurry, reacts with the ammonium chloride solution

to form ammonia gas and a solution of calcium chloride, a waste material. The recovered ammonia from the stills is

re-cycled to the absorbers to saturate more of the purified brine.

Washed and

filtered crude "bicarb" is decomposed in rotary dryers to produce

light soda ash, much of which is sold as a basic raw material to many

industries.

Part of the light

soda ash is processed into dense ash, primarily for the glass industry. Soda ash constitutes one of this industry's

most important raw materials; it combines chemically with sand to become molten

glass, from which a host of products are made.

This Diamond Chemical is also used in processing pulp and paper, iron

and steel, textiles, soap, and hundreds of other products.

Click

here to view a

diagram of the production process.

Chlorine and Caustic Soda

Chlorine and

caustic soda are derived from salt by a method most commonly referred to as

"the electrolytic process"—passage of electric current through a salt

brine solution, decomposing it into gaseous chlorine, caustic soda, and

hydrogen.

Principal raw

materials used are purified brine and electric power. The sodium chloride solution, after

purification, is decomposed in electrolytic cells using direct current. Resultant products are chlorine gas, a weak

caustic solution, and hydrogen.

The caustic

solution is concentrated, settled and filtered to remove salt and other

impurities. Hydrogen gas from the cells

is cooled and either used as a fuel or combined with chlorine to produce

anhydrous hydrochloric acid and muriatic acid.

(See the diagram in Chlorinated Products.) The chlorine gas is cooled, carefully dried

to remove water vapor, compressed, then piped into another section of the plant

for use in chlorination processing operations.

Dry chlorine gas

can be changed into a liquid by further cooling, compressing and

refrigerating. This liquid chlorine is

sold for use in water purification and sewage treatment, and to chemical plants

which use it as a chemical intermediate.

Dried liquid

chlorine is packaged in various containers to meet diverse industrial

demands. Some is put into 100-pound and

150-pound cylinders. Some is loaded in

ton containers shipped either by multi-unit tank cars in lots of 15 per car, or

by tractor-trailer trucks capable of carrying as many as 10 containers. For customers using larger quantities, liquid

chlorine is delivered in single-unit tank cars with capacities of 16, 30, or 55

tons.

Safety and careful

control characterize Diamond chlorine production, loading and

distribution. Control instrumentation is

an effective aid in improving safety, quality and efficiency of production.

Click

here to view a

diagram of the production process.

Chlorinated Products

Chlorinated products

made by Diamond at Painesville are Chlorowax, carbon tetrachloride, and

anhydrous hydrochloric acid.

To produce

Chlorowax, chlorine gas is reacted with paraffin, yielding grades containing

from 40 to 70 per cent of chlorine and ranging from liquids to resinous solids.

Carbon

tetrachloride is produced from chlorine gas and carbon bisulphide. Solvent blends, also made here, are used as

grain fumigants, fire extinguisher fluids, and for special purposes.

Chlorine and

hydrogen gas are used to produce a water solution of hydrogen chloride

(muriatic acid). The dissolved hydrogen

chloride is then stripped from the muriatic acid under pressure, refrigerated

and dried to produce a pure, dry hydrogen chloride gas.

Click

here to view

a diagram of the production process.

Baking Soda and Diamond Crystals

Soda ash is the

starting point in producing baking soda and Diamond Crystals.

In making baking

soda, a solution of soda ash is first filtered to remove insoluble matter, then

fed at a continuous rate counter-currently to a tower, through which carbon

dioxide gas is passing. The combination

of soda ash and carbon dioxide forms a "purified" sodium bicarbonate,

which is separated as a solid from the solution in high-speed centrifuges.

After centrifugal

washing, refined bicarbonate passes through dryers to remove the moisture, then

screened to yield a series of baking sodas for the food industry and related

fields. In recent years, the very-fine-particle

size baking soda has found a new market as the principal ingredient of a

dry-type fire extinguisher.

Diamond Crystals,

like baking soda, also rely on light soda ash as the basic raw material. The ash solution is filtered to remove

insolubles, then evaporated under controlled conditions to yield a crystalline

product, which is separated from the "mother liquor" in a centrifuge.

The crystals are

then washed, dried, and screened before packaging and shipment to many

detergent manufacturers, who use Diamond Crystals as a raw material in

formulating numerous washing and cleaning compounds.

Click

here to view a

diagram of the production process.

Silicate-Detergents

Diamond also

blends alkalies and detergents to produce washing soda and a wide variety of

other alkali cleansers required for specialized applications by our

customers. Also produced here are two

types of metasilicate—crystalline and anhydrous.

The first is

processed from liquid caustic soda and sodium silicate, the second from dense

soda ash and high-grade silica sand.

Both types find wide use in compounding detergents for application in

dairy and bottling plants, for metal-cleaning, and in commercial laundries.

Sal soda, extensively

used for water-softening purposes and as a household cleaner, is also produced

at Painesville. Still other Diamond

products made here are drain pipe opener, bowl cleaner and detergent compounds.

Click

here to view a

diagram of the production process.

Calcium Carbonates

From by-product

raw materials, Diamond produces calcium carbonate in many forms for the paint,

plastics, rubber and printing ink industries among others.

While the flow

diagram appears to be relatively simple, it is somewhat deceiving in that it

fails to indicate the exacting conditions and constant control which must be

maintained to perform the operations required in producing these chemicals. Raw materials for the most part are

by-products of our soda ash operations.

This part of the

Painesville Works, known to Diamond folks and customers alike as the "Pure

Calcium Products" Plant, has won national renown for the qualities of

purity and uniformity.

Click

here to view a

diagram of the production process.

Chromates

Soda ash and

chrome ore are the chief raw materials used to produce sodium bichromate.

Chrome ore

(imported from Africa mostly) is dried and crushed before entering a mixer,

where soda ash and dolomitic lime are blended with the pulverized ore in exact

ratios. This dry mixture is then charged

into oil or gas-fired rotary kilns, where the chrome compound fuses at high

temperature into a clinker.

Upon cooling, the

clinker is leached with water to remove the soluble chrome salts. Classifiers and filters then separate the

residue from the solution, which is next neutralized with sulphuric acid. A strong bichromate liquor is recovered

through filtration and evaporation.

A considerable

quantity of bichromate is sold as a liquid, but some portion of the liquor is

crystallized to produce bichromate crystals.

After drying and screening, they are sold in dry crystalline form.

Many operations

are required to purify the chromate solution, resulting in the production of

by-product chemicals in sufficient tonnage for sale in the industrial chemicals

market. These operations are carefully

controlled from the initial step of pulverizing the chrome ore through the

final stage of preparing the products for shipment.

While the

bichromate liquor is being purified, the first filtering of the original

solution produces aluminum hydroxide; and when the liquor passes through

salt-removing evaporators, these salts are fed through filters and dryers to

produce sodium sulphate.

Chromic Acid is

another chemical produced here. The

finished product, made from sodium bichromate and sulphuric acid, is sold in

flake form. Chromic Acid has many uses

throughout industry, the most important one being electroplating for both

decorative and protective purposes.

The Chromate Plant

at Painesville, one of the largest bichromate-producing facilities in America,

has been completely rebuilt in recent years.

It now incorporates processing equipment of the latest design, together

with facilities providing vastly improved working conditions.

Click

here to view a

diagram of the production process.

Cement

Principal raw

material used by the Standard Portland Cement Plant at Painesville consists of

limestone fines transported from upper Michigan to Fairport, and fines removed

by screening limestone at the Stone Dock.

They are transported by rail to the Cement Plant, where the stone is

pulverized in ball mills with clay harvested from clay pits adjoining the plant

property.

The slurry of

limestone and clay is then stored in large tanks and carefully adjusted to

proper ratios. It is then fed into

rotary cement kilns by two methods—de-watering it by filtering, and by direct

slurry feed.

With kilns fired

at high temperature and using pulverized coal, the limestone and clay decompose

and combine to produce a cement clinker, which is then cooled, pulverized in

ball mills with gypsum, and carefully classified to remove all coarse

particles.

The

finely-pulverized clinker is then pumped as a dry powder into the silos, where

it is stored in batch lots prior to analysis and testing to make certain the

finished product meets customer specifications.

Exacting methods

of chemical control are used extensively in the cement industry and the plant

here is no exception. Control over each

step of the operation is a basic requisite in meeting the high standards set by

the industry.

Production

capacity at the plant has been steadily expanded in recent years. In 1954, for example, capacity was increased

by 380,000 barrels through the conversion of a lime-burning kiln to cement

manufacture. The following year an

additional 320,000 barrels were made possible with the installation of a new

finished cement grinding mill with auxiliary equipment.

Presently under

way is another project which, when completed, will increase capacity by another

800,000 barrels. Thus, within a

three-year period, capacity will have been increased from 1,200,000 barrels to

2,700,000 barrels.

Click

here to view a

diagram of the production process.

Coke and Coke By-Products

Primary function

of the Coke Plant is to produce a high-grade, properly-sized coke for burning

limestone used in soda ash manufacture. Surplus

coke is prepared for and sold to the foundry industry. Coke oven gas, a by-product, is used by other

production units at our Painesville Works.

Several grades of

coal, rail-transported from Pennsylvania and West Virginia, are properly

pulverized and proportioned for charging into the coke ovens. Coal is heated with coke oven gas already

produced until all volatile matter is driven from the coal into collection

headers. Next, the hot coke is pushed

from the oven, quenched with water, screened to various required sizes, then

loaded into hopper cars for shipment to the lime kilns or to our customers.

Recovered coke

oven gas is first scrubbed with water to remove ammonia and water-soluble

salts, then passed through oil scrubbers, which absorb benzene, toluene and

xylene. Finally, the gas flows through

layers of wood chips, saturated with iron oxide. This operation removes sulphur compounds from

the gas. Now purified, it is distributed

throughout the plant for use as a fuel.

Water and wash-oil

from the gas scrubbers are recovered and stripped in steam stills to recover

the ammonia, sulphides, benzene, toluene and xylene.

Click

here to view a

diagram of the production process.

Plant Consumes Raw Materials in Huge

Quantities

A few statistics may help you to

better visualize the scope of our operations at Painesville. In a single day we use

* 100 million

gallons of water, enough to more than meet the daily requirements of the City

of Cleveland.

* 2,300 tons of limestone, enough to fill 40

fifty-ton freight cars.

* 1,000 tons of coal, enough to supply 225

homes for a year.

*

3,000 tons of salt, enough to supply the yearly needs of 650,000

families.

In

addition to these basic raw materials, suppliers from many parts of the United

States and elsewhere send us other raw materials required to operate our

plant. They include silica sand,

limestone fines, gypsum, and chromite ore.

We supply our own clay, salt and purified brine.

Chronology of the

Painesville Works

(A

key to sources is listed at the bottom of this section)

The Beginning and

The End

Diamond

Alkali began operating in 1912 [1]

The

Chromate Plant was shut down in 1972 [1]

The

majority of the Works was shut down in 1976

[1]

The

last remaining operating unit of the Works, the Chlorowax Plant, was shut down

in 1977 [1]

Below

are details for specific plants within the Works:

Main Plant

(On

map above: Soda Products, Washing Soda, Diamond Crystal, Buckeye Soda,

Baking

Soda, Caustic Soda, Pure Calcium Products)

Soda

Ash began operations 1912 [D]

Caustic

Soda began operations 1915 [D]

Bicarbonate

Soda began operations 1918 [D]

ceased

operations 1976 [1]

sold

for scrapping/demolition 1978 [1]

Chlor Alkali Plant

(On map above: Silicates, Electro-Chemical

Products)

built

1929, began operations 1929 or 1930 [D,1]

ceased

operations 1976 [1]

sold

for scrapping/demolition 1978 [1]

Hydrochloric Acid Plant

(On map above: Chlorinated Products)

began

operations 1930 [1]

ceased

operations 1976 [1]

sold

for scrapping/demolition 1978 [1]

Carbon Tetrachloride Plant

(On map above: Chlorinated Products)

built/began

operations 1933 [1]

ceased

operations 1976 [1]

sold

for scrapping/demolition 1978 [1]

Chlorowax Plant

(On map above: Chlorinated Products)

built/began

operations 1944 [1]

ceased

operations 1977 [1]

sold

for scrapping/demolition 1978 [1]

Coke Plant

built/began

operations with 1 battery of 23 Koppers-Becker ovens 1924 [D,P,M,1,2]

additional

battery of 23 Koppers-Becker ovens built/began operations circa 1937 [M,K]

sold

to Erie Coke & Chemical Co. 1976 [1,2]

ceased

operations 1982 [1,2]

sold

for demolition 1983 [1,2]

demolished

1986-1988 [1,2]

Standard Portland

Cement Plant

PLANT

A

(On

map above: Cement Plant)

built/began

operations 1924 or 1925 [D,1,3]

closed

1961 [3]

structures

used for cement storage until 1968 [3,T]

structures

left idle until 1980 [conjecture]

sold

to Aluminum Smelting & Refining Co. 1980

[4]

leased

to Cousins, Inc. 1992 [4]

sold

to Cousins, Inc. 1997 [4]

sold

for demolition 2004 [4]

demolished

2005-2006 [based on 2006 aerial

photos]

PLANT B (On map above: Cement Plant

Expansion; converted portion of Caustic Soda building)

began

operations 1954 [D]

closed

1964 [3]

structure

left idle until 1978 [conjecture]

sold

for scrapping/demolition 1978 [as part of Caustic

Soda building]

Chromate Plant

(On map above: Chromium Chemicals Plant)

built/began

operations 1931 [1,D]

ceased

operations 1972 [1]

plant

demolished 1972-1973 [based on 1973 aerial

photo]

area

sealed 1978-1980 [1]

Magnesium Plant

(Not on map above: located east of Painesville

Works at 720 Fairport-Nursery Road [5])

built/began

operations 1942 [D,6]

deactivated

1945 [D]

reactivated

1951 [D]

deactivated

1953 [D,6]

sold

in two parts 1963 [5]

Western 2/3 Portion

sold

to US Rubber (Uniroyal) 1963 [5]

ceased

operations 1999 [6,7]

subsequently

demolished [based on 2002 aerial

photo]

Eastern 1/3 Portion

sold

to Pillsbury 1963 [L:11B-040OLD]

sold

to Glyco 1969 [8]

Glyco

merged into Lonza 1986 [9,10]

sold

to Twin Rivers Technologies 2002 [9,10]

Another

industry located adjacent to the Painesville Works but that was never part of

Diamond Alkali/Shamrock will be included here since US Rubber (Uniroyal)—who

bought part of the Diamond facility above—at one time owned this facility as

well:

Glenn L. Martin Chemical Company

(Not on map above: located on eastern edge of

Diamond property at 900 Fairport-Nursery Road [11])

built/began

operations 1947 [11]

sold

to US Rubber (Uniroyal) 1949 [7,11]

ceased

operations 1975 [11]

sold

to Dart Cartage (Dartron) 1979 [11]

sold

to Crompton Manufacturing 2001 [L:12A-051]

Sources

1 Ohio EPA DSPW Site: Director's Final

Findings and Orders, 9/27/95

2 Ohio EPA DSPW OU6 Site: Director's

Final Findings and Orders, 7/13/06

3 FTC Docket 8572, 72 FTC 700: In the

Matter of Diamond Alkali Company, 10/2/67

4 Ohio EPA DSPW OU2 Site: Director's

Final Findings and Orders, 7/13/06

5 US Army Corps of Engineers Painesville

Site: Engineering Valuation/Cost Analysis, June 1998

6 US Army Corps of Engineers Painesville

Site: Final Record of Decision, April 2006

7 Ohio EPA Uniroyal Site: Director's

Final Finding and Orders, 5/14/99

8 "Glyco Buys Pillsbury

Plant," Soap & Chemical Specialties, March 1969

9 "Lonza Exits Fatty Acid

Manufacturing With Plant Sale," Chemical Market Reporter, 9/16/02

10 "Lonza Sales [sic] its Painesville

Fatty Acids and Glycerine Plant," Lonza Press Release, 1/7/03

11 Dartron Corp v Uniroyal Chemical Co.,

893 F.Supp. 730, 1995

D The Diamond Story at Painesville, 1956

P Trade Publications: American Gas

Association Fifth Annual Convention Proceedings, 1923

and Gas Industry, Vol.

24, 1924

M Fairport, Painesville & Eastern

Valuation Maps

K Koppers-Becker Coke Ovens, 1944

T Testimony from ICC Docket 23980

L Lake County Tax Map

Sources

1, 2, 4, and 7 are available for free download on the Ohio EPA website here.

Sources

5 and 6 are available for free download on the ACE website here.

Sources

3, 11, P, and K can be found at any large/major library.

Sources

8-10 can be found on the internet.

Source

D is discussed above; I am not sure where any other copies can be obtained.

Sources

M and T are available from the National Archives (as discussed on my FP&E Resources

page).

Source

L is available on the Lake County website (as discussed on my FP&E Maps page).

Notes and Observations

I have posted some aerial photos of the Diamond's

facilities on my flickr account; click here

to view them.

As per references in

numerous ICC documents, the FP&E did not provide intra-plant switching

services for the Diamond. However, that

statement does not mean that much: Basically, due to the nature of the

Diamond's product shipments and the layout of the Painesville Works, for the

most part the only activity that was necessary on the Diamond's tracks was the

spotting of empty or loaded cars—and any switching that had to take place to

get cars ready for spotting was handled by the FP&E on their yard

tracks. Even in cases where cars were

unloaded at one part of the plant and then taken to another part of the plant

to be loaded (and vice-versa), such switching moves were deemed FP&E

intrastation moves (the station being "Alkali"). But though the FP&E handled most of the

switching duties that needed to take place for the Diamond, the Works still had

a need to move cars within the confines of its facilities, and through the

years they used various small industrial locomotives for those duties—such as a

Plymouth 30-tonner, a couple GE 25-tonners, and a couple GE 45-tonners. One of the 45-ton units was used to move the

quench car at the Coke Plant, and in this photo

from 1951 (a portion from one of the aerial photos I refer to above), you can just

make out the GE switcher moving the quench car between the coke ovens and the

coke wharf (at the base of the large smoke stack in the center of the

photo). Another 45-tonner in a nice

green-and-yellow paint scheme was used to move FP&E hoppers at the

Diamond's Stone Dock. A close-up picture

of that switcher in the FP&E's West Yard can be viewed here; and a more

recent picture of the same switcher—albeit, permanently out of commission—can

be viewed here.

In the book Trackside

Around Eastern Ohio (more about this book near the bottom of this

page), on page 59 there is a photo caption that reads, in part: "The

limestone came off the lake at the dock and was used in the making of coke at

the Diamond Alkali plant …." As can

be seen from the information above, this is incorrect: the limestone was used

primarily for making soda ash, and secondarily for making cement. On page 60 of the same book there is a photo

with an accompanying caption that reads, in part: "Diamond Alkali … was a

major producer of coke for the steel industry.

Here Dave catches #104 and #107 making up a drag for the N&W at

Perry. The Diamond Shamrock chemical

plant closed in the 1970's dealing a blow to the FP&E but the coke plant

remained into the 1990's …." For

the following reasons, these statements are incorrect:

1) As explained in "The Diamond

Story" section above, the Diamond was a producer of coke primarily for

itself; and though it did sell surplus coke to outside customers, from the

materials I have read the Diamond would not be considered a major

producer. The Diamond produced

"furnace coke," and in 1973 when the Coke Plant was running at peak

capacity (the previous year both coke batteries had been rebuilt) it produced

about 680 tons of coke per day—of which about 200 tons went to the lime kilns,

leaving roughly 480 tons available to be shipped to outside customers each day. When the Diamond sold the Coke Plant to Erie

Coke & Chemical, the new owner produced "foundry coke" which,

because of the longer coking time required, reduced the plant's total

production amount to about 425 tons of coke per day. These daily production amounts may sound like

a lot, but when compared to a true major coke producer such as the US Steel

Clairton Coke Works, which in 1980 produced more than 16,000 tons of coke per

day (and in the 1940s and 1950s produced 21,000 tons of coke per day), then the

Diamond's Coke Plant was definitely a minor producer.

2) In the photo the caption refers to, it is

implied that the hoppers in the photo are going to be interchanged with the

N&W for shipment to a customer.

However, the cars in the photo are the FP&E's 800-series hoppers,

which, as I discuss on my FP&E

Freight Car Roster page, were limited to use on FP&E rails only—meaning

that the hoppers in this photo are actually in the midst of an intrastation

move of coke from the Coke Plant (on the east side of the Painesville Works) to

the lime kilns (on the west side of the Painesville Works).

3) As shown in the Chronology section of this

page, the Coke Plant ceased operations in 1982.

Created

by Scott Nixon

July

2009

Updated: October 2010, April 2011, September

2021